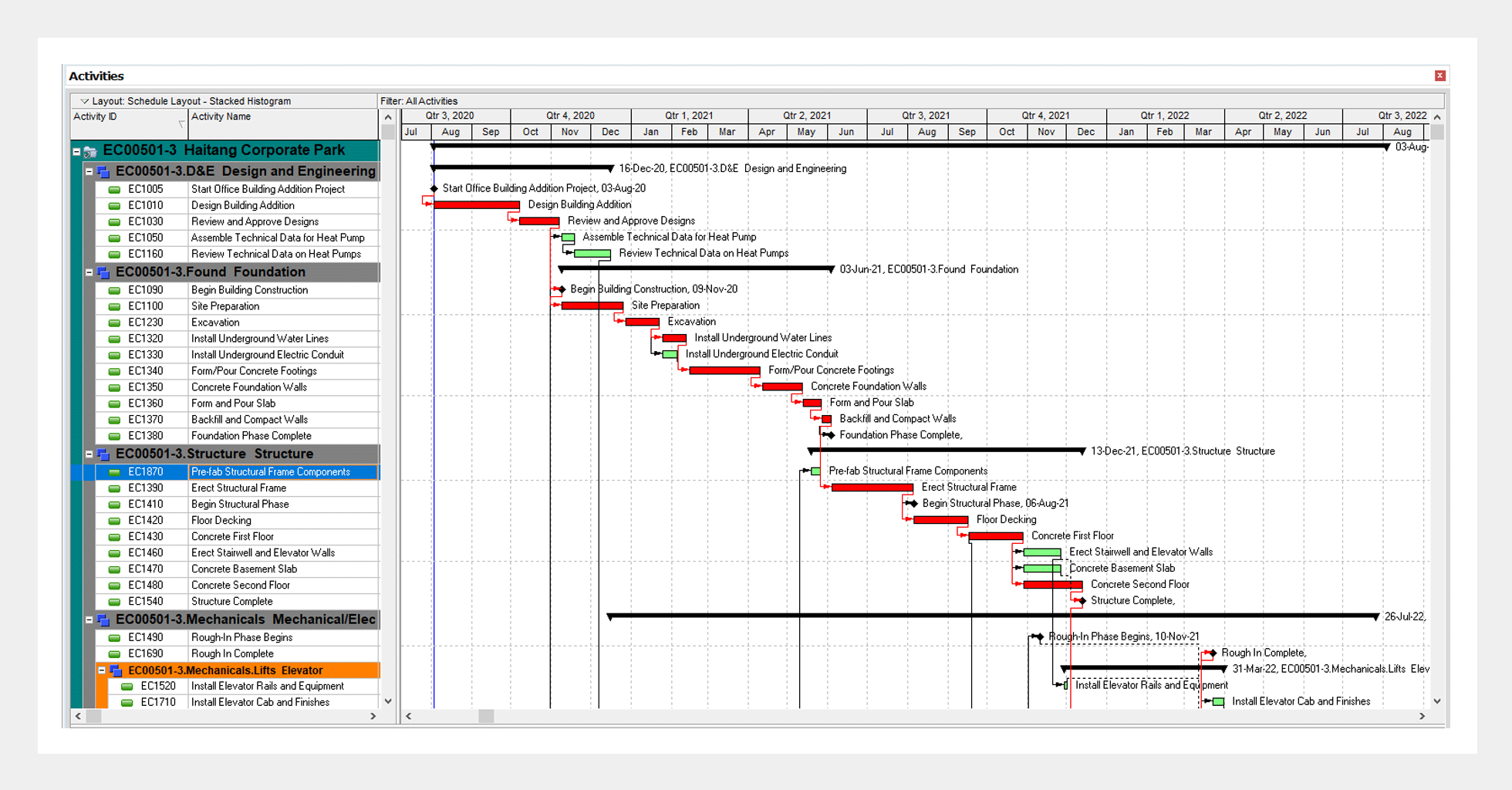

Four tests must be satisfied before recovery for delay costs will be allowed— a contractor must prove that the delay was (1) excusable, (2) compensable, (3) critical, and (4) non-concurrent. The third and fourth tests require some form of CPM based schedule analysis.

A delay, or acceleration, of work along the critical path will affect the entire project.

Methods to analyse a delay claim

There are four primary methods of analysing a delay claim using a CPM schedule. All four methods rely on some comparison of the as-planned schedule to the actual as-built schedule or events. Two methods are primarily used after the project is completed and two methods are used during construction.

Method 1

The first approach requires a determination of which events the other party is responsible for and then removing them from the as-built schedule by manipulating the scheduling software. In essence, delays caused by the owner are removed from the schedule then a comparison is made to the as-planned schedules completion date. This method is used after the project is completed. If the collapsed as-built completion indicates that the collapsed project completion date is equal or less than the as-planned schedule the owner is responsible for the delays. This method is referred to as the “collapsed” as-built schedule method.

Method 2

The second method involves a selection of specific time periods when major delays occurred for an “as-planned” versus “as-built” comparison. Rather simply collapsing out the owner caused delays, this approach involves a more in-depth analysis of how each delay period impacted the critical path activities. Once an analysis of the first major delay is made, then those conclusions become the baseline for determining how the subsequent delays impacted the project. This approach is used after the project is completed.

Method 3

The third method involves modifying the “as-planned” schedule. The method involves either modifying the as-planned schedule by modifying the schedule to reflect the critical delays for which the owner is responsible or alternatively by modifying the schedule to reflect the critical delays for which the contractor is responsible. A comparison of the original “as-planned” schedule to the modified schedule should indicate the number of additional days that are attributable to the owner. This method is typically used before a project is completed. It should be noted that the courts have questioned the validity of such an approach since it fails to accurately measure the impact of the delays on the critical path.

Method 4

The fourth method involves the use of fragnets, which are fragments of a CPM network. In essence, new partial CPM networks are created for the periods or events that are being evaluated. Once the fragmented portion of the schedule is completed, it is then added into the current “as-built” schedule. At which point, an evaluation of the delay can be made in relationship to the ongoing activities. The fragnet approach is typically used during construction.

Conclusion

Delay analysis is not limited to the four methods. There are several variations on the four methods. Before a court will accept whatever method is chosen, the proponent of the analysis method must be able to establish that the approach identifies how the delay impacted the actual completion of the project. Only those delays which delay the actual completion of the project are on the critical path. Finally, a properly prepared and updated CPM based schedule can be the key method for proving the other party’s responsibility for delays.